Newsletters

Q&A With Wendy Chin-Tanner

New Information about Upcoming Book Related News

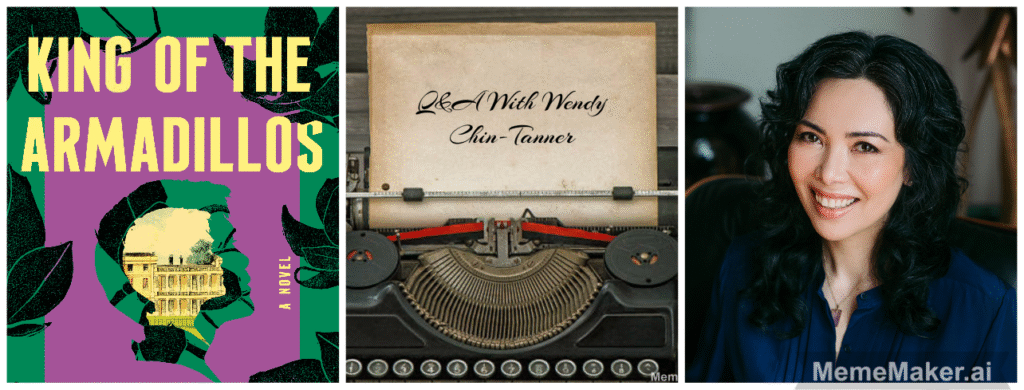

Q&A With Wendy Chin-Tanner

I’m happy to be doing this Q&A with author and poet Wendy Chin-Tanner! Wendy is the author of the poetry collections Turn and Anyone Will Tell You & the novel King of the Armadillos. King of the Armadillos is a Louisiana Literary Award Winner! She has had poems and essays featured in numerous publications including The Academy of American Poets, The Rumpus, The Kenyon Review, Salon, and Literary Hub. Wendy was also featured in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, Ms. Magazine, and Good Housekeeping, and on ABC News Live Prime with Linsey Davis and NPR. Here is the link to her website to read more. https://wendychintanner.com/bio

Q: Would you please give a brief description of your work beginning with your novel King of the Armadillos?

A: Set in the 1950s, King of the Armadillos follows the story of Victor Chin, a Chinese American teenager who’s diagnosed with Hansen’s Disease (aka leprosy) and sent from NYC to the famous federal leprosarium in Carville, Louisiana where he must be quarantined until–or unless–he’s cured. At first, he feels like he’s been banished to a prison in the middle of nowhere, but soon, he finds a community of patients from all over the country and all walks of life who become his friends, mentors, and rivals. Carville is a place of contradictions, of institutional control on the one hand, and freedom from the segregation of the Jim Crow South on the other. Meanwhile, back in New York, Victor’s father’s relationship with his Jewish mistress is becoming more serious. Victor’s elder brother Henry despises her for trying to replace their mother left behind in China, but he himself is in love with a married woman. At Carville, as Victor’s body begins to heal, he falls in love for the first time and discovers his calling as a musician. But when the chance of getting well and going home becomes a reality, Victor must make some difficult choices.

King of the Armadillos is a coming-of-age story, but it’s also the story of a complicated Chinese American family that was inspired by my own. Like Victor, my father also had to leave my grandmother behind in China when he went to live with my grandfather at the back of the laundry he owned in the Bronx. And just like Victor, when he was a teenager, my dad was diagnosed with leprosy and sent to Carville where he stayed for 9 years, from 1954-1963. My dad was instrumental in helping me research this book. And so, Carville is a part of who I am, too.

The book asks three core questions: How do we define family? How do we negotiate other people’s needs with our own? And how do we heal from trauma? While exploring the healing power of art, it also uncovers a forgotten piece of Asian American history, explores the impact of disease stigma, immigration, and anti-Asian racism on families, and teases out nuances of class and gender.

Q: Where do your ideas for your poems and book come from? What was the transition going from writing poems to then writing a full-fledged novel?

A: Storytelling and linguistic expression are the main ways that my brain processes my experience. Everything that happens to me, everything I read and watch and listen to, everything in my family and cultural history percolates in my subconscious and eventually bubbles up into scenes, images, bits of dialogue, clusters of words that make the right kind of music.

The transition from poetry to a novel was rough! Before writing King of the Armadillos, I’d never even written a short story. At first, I tried to bridge the gap by leaning on my experience with writing academic papers in Sociology, which I’d studied in grad school and taught at the undergraduate level for many years. I started gathering research and since the material was historical and biographical, I figured the book should be creative nonfiction. But nonfiction isn’t what I wanted to come out with. I realized that in order to tell the story I wanted and needed to tell, I was going to have to teach myself how to write a novel.

For a while, I felt kind of frozen, unsure of how to navigate the process, afraid of mishandling the topic, and confused about how to enter the narrative. After drafting the first scene where Victor leaves for Carville, I had to put the story down and let it marinate for a good long while, during which time I wound up writing my second poetry collection, Anyone Will Tell You. I don’t know if other writers who work in multiple genres experience this, but my projects are kind of like feral cats. They come to me when and how they want to, and they don’t give me much of a choice about which one needs attention.

When it was time for King of the Armadillos, I had to follow the path of least resistance by going back to what I already knew how to do–drafting a bunch of poems, finding the threads that connected them, and arranging them into narrative arcs that would cohere into a book. So as not to spook the feral cat and coax it to stay, I started with little vignettes that I treated as prose poems without worrying about where they might belong in the story.

I tend to approach my writing from the inside out. The first draft for me is always about listening. Whether it’s a poem, an essay, or a novel, I turn my ear inward and let my subconscious talk to me. Then I just transcribe what it says–snippets of dialogue, phrases, gestures, sensory details, character descriptions, plot points, and sometimes even whole scenes. After that, I turn what I’ve got into bigger scenes that build further into chapters, and finally, into story arcs as I find the connective elements for the plot. My early drafts are incredibly messy and loose. King of the Armadillos took me twenty drafts to write. I hope my new book is easier and faster!

Q: How long did it take you to write King of the Armadillos vs your books of poems?

A: King of the Armadillos took FOREVER. Well, almost. Between the first words I put on the page and the full manuscript, about eight years passed. There were a few reasons for this. Life was probably the biggest one.

Shortly after I began writing the book, when my husband and I were trying for a second child, I suffered three miscarriages and went through two years of fertility treatment. On our last round, I got pregnant with our younger daughter.

During that time, my imaginative and literary focus shifted from the King of the Armadillos story to processing what was happening to me in the form of poetry. The poems that came out of that period wound up in my second poetry collection, Anyone Will Tell You.

I returned to King of the Armadillos when that book was done and my baby was two, which meant I could devote more uninterrupted hours to the sustained focus that fiction requires while she was at nursery school and my older daughter was at elementary school. I can more easily dip in and out of poetry, which explains, now that I think about it, why I wrote both of my poetry collections when my kids were babies. So, I’d say that the active process of writing my novel took about five years, whereas the process of writing both my poetry collections took about two.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from reading your poems and novels after they turn the last page whether it’s important lessons, resonating with characters and stories or evoking strong emotions?

A: I think the common thread in all my work is the invitation to empathize with experiences that might not be our own. When we read, when we are transported to other times, other places, and other bodies, we get to walk in other people’s shoes and feel what other people feel. Through that experience, we learn that people are people wherever we are.

Whether we’re in an 18th Century castle in France, a 21st Century skyscraper in Dubai, or a 1950s leprosarium in Louisiana, we all have the same human needs and foibles. We all want to love and be loved. We all make mistakes and must live with their consequences. In King of the Armadillos, for example, I portrayed Victor and his Carville friends in the full breadth of their humanity in hopes that readers would see that they are, just like the rest of us, far more than their circumstances. I hope, too, that I was able to bust some myths about leprosy.

Leprosy is perhaps the most stigmatized and misunderstood disease on earth, so much so that the word leper is a metaphor for stigma. One of my goals in writing about it was to challenge not only leprosy’s medical stereotypes, but also its tendency to dehumanize its sufferers and reduce them to their illness.

People with Hansen’s disease aren’t “lepers.” They’re just people with a disease that’s entirely curable and only minimally contagious. In fact, 95% of the human population is naturally immune. And even 5% of those who are susceptible require close and prolonged contact to become infected.

Disease progression is also very slow. The incubation period can take up to twenty years, and it takes years after exposure to become symptomatic. The ideas we get from Leviticus and popular culture are riddled with misconceptions.

Hansen’s is a bacterial infection that initially manifests as lesions, which can become systemic if they’re left untreated, affecting the extremities first, like hands, feet, noses, and ears, causing insensitivity. The common belief that leprosy makes people’s limbs fall off is a myth that stems from the fact that in some cases, when the nerves become so insensitive that a patient can no longer feel parts of their body, they become prone to injury and subsequent infection, which can result in amputation. Late-state disease can also cause bones to retract, and can affect the lungs and the eyes, causing blindness in some patients. But the kinds of disfigurements that the public associates with leprosy happen only when the disease is left untreated for many years. This is one of the many reasons that stigma around Hansen’s disease is so harmful, because it prevents people, even today, from coming forward and seeking medical care.

Q: If there were a sequel to King of the Armadillos what would the characters be doing right now?

A: Wanna know a secret? I originally wrote an epilogue for King of the Armadillos that wound up on the cutting room floor. I can’t tell you everything that was in it because of spoilers, but it takes place about ten years after the ending, in the late 1960s. Victor is back in New York and married to Zelda, a cool hippie chick he met in college where they were both studying music. He’s got a day job at an ad agency writing jingles for commercials, but on the side, he composes and plays jazz music with his friend Frank, a band leader whose dad played double bass for Duke Ellington. Through Frank’s connections, they get their first big break, filling a last-minute spot in a prestigious music festival. Victor composes a twenty-minute piece entitled “King of the Armadillos” that gets a rave review in The New York Times.

Q: Can you reveal any stories and poems you are writing right now, or is it too early to discuss them?

A: I’m working on a new novel, but instead of historical fiction about leprosy in the 1950s, this one is a satirical comedy about perimenopause set in 2020. Linda is a wife, mother, and graduate student on the verge of a midlife crisis. Her life is a hot, sweaty mess, her marriage is in the toilet, and her ex-supermodel mom is driving her nuts. When the pandemic hits, the shit hits the fan!

Think All Fours meets Crazy Rich Asians, with a side of Sense and Sensibility. The tone of the humor is like Arrested Development, Schitt’s Creek, and Broad City, so it’s super fun to write. I love texting little excerpts to my friends to make them laugh.

Q: If Hollywood were to get the rights to King of the Armadillos, who would be your dream cast to play the characters you created?

A: I love this question so much and I love thinking about it! I’d cast Ben Wang as Victor, Harry Shum Jr. as Sam, Jenny Slate as Ruth, James Tang as Henry, Jackson Geach as Donny, Maya Hawke as Judy, Lucius Hoyos as Manny, Andy Samberg as Herb, and Jamie Lee Curtis as Sister Helen.

Q: How does it feel knowing that King of the Armadillos is a Louisiana Literary Award Winner? Also Congratulations! It must be a dream come true!

A: Thank you so much! One of the things I wanted to do in King of the Armadillos was to shine a light on the remarkable achievements of the community that existed at Carville. It was truly a triumph of socialized medicine, a model for institutions done right, and because barely anyone knew about it, Carville was destined to become a lost piece of American history.

Having the book recognized by the State of Louisiana ensures that Carville and its people will never be forgotten. I was thrilled to be able to go to the awards ceremony with Elizabeth Schexnyder, the curator of the National Hansen’s Disease Museum at Carville, as my guest of honor. Not only did she provide me with all the archival materials I could ask for, but she also helped me find out exactly how things were done at Carville in the 1950s.

On a personal level, the award means the world to me, because even though I might look and sound like a Brooklyn girl, my roots run deep in Louisiana soil. A big piece of my heart and family history belongs there. The fact is, I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for Carville, and as a second-generation product of its culture, without it, I wouldn’t be the person that I am either.

Q: What’s it like having your poems and essays featured in so many publications? What was it like being featured on ABC News Live Prime with Linsey Davis and NPR?

A: I’ve been writing and working in publishing for over twenty years, so the list of publications you see in my bio is the result of steady perseverance through the tsunami of rejection and the systemic obstacle course faced by writers from marginalized identities, especially those of us who are parents and caregivers.

Getting featured on ABC and NPR were such amazing opportunities to introduce America to Carville and to advocate for Hansen’s disease awareness on larger platforms. The fact that there are still so many myths, so much misinformation, and continued stigma around leprosy means that my job there is far from done.