Newsletters

Q&A With Walter B. Levis

New Information about Upcoming Book Related News

Q&A With Walter B. Levis

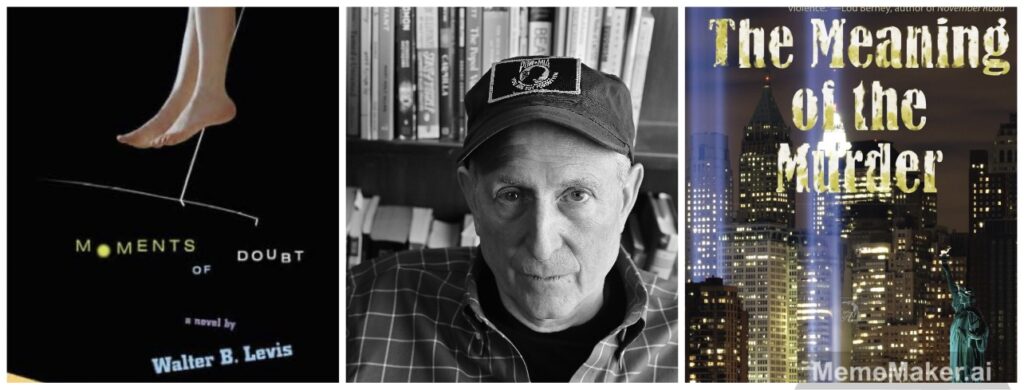

The wonderful Rachel Tarlow Gul was kind enough to connect me with author & former crime reporter Walter B. Levis the author of Moments Of Doubt & his new release The Meaning of the Murder. The Meaning of the Murder was released on August 5th and is available now wherever you get your books. Walter’s articles in his career as a crime reporter have appeared in The NY Daily News, The National Law Journal, The Chicago Reporter, The Chicago Lawyer, The New Republic, Show Business Magazine & The New Yorker.

Q: Walter, welcome to Book Notions! Would you please give a brief description of both of your novels, The Meaning Of The Murder & Moments Of Doubt?

A: My first novel, Moments of Doubt, was based on my first career—I was a tennis pro. I had once dreamed of playing in Wimbledon, but the closest I came was a number seven ranking in Illinois, a scholarship to play in the Big 10, and some tiny prize money in what used to be called the “satellite” circuit, which were the small qualifying tournaments for the big time events. So for about ten years I earned a living as a “teaching pro,” which is the term we used to distinguish ourselves from the “real players.” Teaching pros, in those days, took a skills test given by the United States Professional Tennis Association, where we had to demonstrate our shots and give a sample lesson. Right after graduating from the University of Wisconsin, I moved back to Chicago, my hometown, got the USPTA certification, and started working at private clubs in the city and its suburbs.

All of this informs Moments of Doubt, particularly the setting. The peculiar culture of country clubs fascinated me, and it shapes the story’s events and influences the characters’ behavior. The manicured courts, polite conversation, pleasing sound of balls hitting the strings of a racket, this surface-level order and calm conceals the chaos of status anxiety, vanity, aging, exclusion, and, yes, the violence that haunts the lives of the characters in this novel.

Moments of Doubt, however, is not a crime novel. It’s a coming-of-age story. In fact, one review described the protagonist as “a Jewish Holden Caulfield.” The plot centers on a young man’s entanglement with three women—one he’s supposed to marry, one he wants to marry, and one who’s already married to a Jewish gangster. The connection to Holden Caulfield was completely unconscious, but looking back I can see that Holden’s worldview is, in a sense, a perfect fit for the kind of crime fiction I’m interested in. Like many cops I’ve known, Holden sees the world as essentially corrupt, phony, and cruel. But beneath a thick layer of cynicism, there’s genuine vulnerability. At the end of the novel, Holden wants to be “the catcher in the rye,” the one keeping children safe, helping them avoid the danger of falling into the morally compromised world of adults. The job of a cop is something similar: protect the innocent.

These issues are present in my new novel.

The Meaning of the Murder dramatizes how a crime is never just an isolated act—it ripples outward, changing all who come into contact with it. Although the narrator “sounds” nothing like Holden, I think Holden would recognize that what’s at stake here isn’t just solving a mystery—it’s about what violence does to the human soul.

The story centers on a Jewish family that unknowingly becomes entangled in terrorism when the father, a bank compliance officer, discovers that his bank is violating OFAC laws and funding terrorists in the Middle East. He alerts the bank’s top brass, but they ignore him. After struggling with the conflict between his position as a fully assimilated member of his professional community and his moral obligations as a man and a Jew, he becomes a whistleblower and contacts the DOJ. The night before his deposition, he disappeared behind his wife and three daughters.

Eliana Golden, the middle child, was thirteen when her father disappeared. Years later, after surprising her family by joining the NYPD, she meets a mysterious and alluring soldier—a man who is far more dangerous than Eliana, and everyone except those at the highest and most secret levels of the U.S. government, understands. And he knows exactly what happened to her father.

What follows is a journey into the depths of America’s covert war against terrorism, but for all its geopolitical backdrop, the novel is ultimately intimate. It’s about love: between a father and a daughter, between sisters bound together by loss, and between a husband and wife trying to hold on to each other in the face of fear and doubt. This complicated relationship between love and violence—how love endures not as a shield against the darkness of violence, but as a reason to keep going in the face of it—that’s the emotional core behind this book.

Q: Is it fair to say that your time as a crime reporter helped influence writing both of your books?

A: Moments of Doubt, as I’ve said, was written before my journalism career, but The Meaning of the Murder grows directly out of my work as a crime reporter.

It brought together the roles of journalist and novelist. The story dives deep into the external world of modern counterterrorism and writing it required extensive research and interviews. But the novel is ultimately intimate. It’s an exploration of what happens to a family that unwittingly finds itself caught in the global war on terror. I’m interested in the inner lives of the characters, their hopes, dreams, fears, and longing for love.

This shift “from the outer to the inner” is, for me, what I’d call a movement from being a “crime reporter” to “writing crime fiction.”

As a journalist, you’re out in the world—asking questions, chasing facts. Some days I stood outside courtrooms furiously scribbling quotes. Other days I knocked on doors hoping the next of kin would give me a comment. I once trailed a probation officer making surprise home visits. I went to the city morgue. The state prison. I listened to victims, suspects, cops, attorneys, and mothers who would never again see their sons.

And always—always—the job was to get the facts. A reporter, especially on the crime beat, lives by verification. No speculation. No filling in emotional blanks. It wasn’t my job to interpret a suspect’s expression or wonder what a mother whispered at her child’s grave. If I didn’t hear it, see it, or record it, it didn’t go in the story.

As a novelist, the work is very different. I am free to focus on the inner life—and to use my imagination. Instead of asking for a quote to capture what a person feels, I can step directly into another’s point of view and imagine what this person might be feeling right now. This power of imagination which makes empathy possible—is exhilarating and deeply humanizing.

In that sense, fiction writing reminds me of what many actors say about their craft: the goal isn’t to perform a character but to inhabit them—to discover what it feels like to live inside another skin. That’s what fiction allows. It’s not about impersonation; it’s about immersion. And when it works, you’re no longer inventing a life—you’re listening to it.

I still remember the moment that drove home the distinction between a journalist’s world and a novelist. Years ago, I was interviewing Richard M. Daley, then mayor of Chicago, about his approach to crime. His father, who had served as mayor for twenty-one consecutive years, had been a famous “machine politician” known for his blatant practice of patronage and exchange of favors. As if to distance himself from his father’s legacy, the younger Daley had recently hired a team of squeaky-clean lawyers from elite schools to serve as city attorneys.

The interview yielded a good article—but one detail never made it into print. The entire time we talked, Daley compulsively chewed gum—one piece after another, discarding each after only a minute or two. He went through an entire pack during our conversation. I never asked about it because it wasn’t relevant to the story. But I couldn’t stop wondering—was it a nervous habit? A coping mechanism? Just a bad taste in his mouth? That’s the kind of question journalism doesn’t always have room for, but fiction does.

Fiction allows you to embrace ambiguity. You can follow an emotional thread even when it leads somewhere uncomfortable.

But this is important: the gears shift in both directions. I’ve been writing fiction now for many years, and the more time I spend in the inner world, the more fascinated I am by outer realities—the forces beyond our control that shape how we feel and what we do. Ultimately, the interplay between inner and outer is what fuels a story.

For me, the move from crime reporter to crime novelist also carries a common thread: moral inquiry. What happened? Who’s innocent? Who’s guilty? That’s the reporter’s task. But the novelist can go further asking to what extent a crime stains not just the perpetrator, but the society that produced them. I think of crime fiction not just as a genre of suspense but of moral reckoning.

Many crime novels focus on the procedural—the forensics, the clues, and the pursuit of justice as a linear path. But, for me, crime fiction is not merely about solving a mystery; it is about reckoning with what crime does to the human soul. A crime is a rupture, a wound in the moral order. I want to push the genre’s boundaries, to tell stories where crime is not only a puzzle to be solved, but a crucible that reshapes those who encounter it. Rather than focusing primarily on solving crimes, I want to confront the psychological and moral consequences of those crimes. To me, crime fiction is not only about bringing wrongdoers to justice but about understanding the cost of justice itself and the ways it changes those who seek it.

Journalists, of course, can explore these questions of justice, and good journalists do. So I don’t want to overstate the difference between being a crime reporter and writing crime fiction. In the end, it doesn’t matter whether you’re chasing facts or following your imagination. What matters is the seriousness with which you take the craft—and the quiet, persistent struggle to write something that’s honest and well made.

Q: What do you hope readers learn once they finish reading your books? What emotions do you hope readers feel?

A: At its core, The Meaning of the Murder is about what happens when ordinary people are thrust into extraordinary circumstances—when a family suddenly finds itself caught in the vast, unrelenting machinery of the global war on terror. The story delves into the uneasy boundary between criminal acts we recognize—murder, corruption, betrayal—and the far more complex, often invisible forces of political violence.

One way to answer what I hope readers learn and feel is to talk about the book’s title. The opening epigraph of the novel is a passage from Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl, who survived Auschwitz, published the book in 1946. I first read it in college, returned to it after 9/11, and again during the pandemic. Each time, it struck a deeper chord.

The popular takeaway is that meaning can be found even in the face of suffering. But what moves me most is Frankl’s more subtle insight: we shouldn’t ask what the meaning of life is—we should recognize that life is asking us. Meaning isn’t something abstract to be discovered; it’s something we answer for. It’s personal, situational, and inescapably moral. Our lives, Frankl writes, are questions to which we must respond.

As I’ve described above, the plot of my book involves a father who becomes a whistle-blower after learning his bank is funding terrorism. The night before his deposition, he disappears. Years later, his three daughters are still trying to make sense of what happened. One represses, one is paralyzed, and one becomes obsessed. Each, in her own way, is trying to make meaning. For each, the meaning of the murder is different.

That, for me, is the core of the book: meaning is shaped not only by what happens, but by who we are and how we respond. The relationship between moral responsibility and our personal lives is not theoretical. It’s immediate, intimate, and always unfolding.

I suppose this could be said of every era in history, but it feels to me that we are living right now in a particularly acute moment of reckoning.

Q: What was it like being a crime reporter and having your articles appear in The NY Daily News, The National Law Journal, The Chicago Reporter, The Chicago Lawyer, The New Republic, Show Business Magazine & The New Yorker?

A: As I’ve said, I loved being a journalist but ultimately found myself drawn to the world of the imagination and its possibilities for exploring the inner life of characters. This shift led me to focus on writing fiction (and supporting myself by teaching). That said, my journalism career also involved lots of work that had little to do with crime, such as writing critical reviews (Show Business Magazine, The New Yorker), covering religion, housing, and race (The Chicago Reporter, The New Republic), and many feature articles about various aspects of life in the legal profession (The Chicago Lawyer, The National Law Journal). Also, not listed here, and a very formative part of my career, is the time I spent living in Binghamton, New York, and working on a daily newspaper (The Binghamton Press & Sun Bulletin), where I wrote extensively about overcrowded prisons. To anyone interested in writing, I’d recommend any kind of work in journalism—it can be very satisfying. And we need good journalists!

Q: Which characters and scenes did you enjoy creating in The Meaning of the Murder? Eliana & Savoyian are interesting characters.

A: I’m glad you find Eliana and Savoyian to be interesting. They are the book’s two main characters. But the phrase “enjoyed creating” doesn’t quite fit the experience of writing for me. Sinking into the lives of fictional characters always involves a certain struggle and angst—so not quite “enjoyment.” But your question brings me back to the issue of why I wrote the book in the first place.

The inspiration for The Meaning of the Murder stems from one of the most pivotal and haunting moments of my life: 9/11. I was in the Bronx with my three-year-old daughter, far enough from Ground Zero to be physically safe, yet close enough to feel the weight of what was happening. The eerie silence, the faint scent of something unnatural in the air, and the fighter jets streaking across the sky, all of it made me realize how vulnerable we really were. Perhaps I was one of the so-called “naïve Americans,” but for the first time in my life, I felt the threat of war. We are under attack, I thought, and acknowledging this gave me a deep, unsettling helplessness. There was nothing I could do except protect my daughter and shield her from the images on television. Meanwhile, I knew that men and women in uniform—first responders—were rushing toward danger.

That moment made me think of my father. During World War II, he volunteered as a paratrooper—not for the combat pay, but because he wanted to confront the evil of Hitler directly. He didn’t want to sit on the sidelines. On 9/11, I understood that urge. I wanted to take action. But how? That question stayed with me, and over time, it evolved into the driving force behind my novel.

The inspiration for the characters of Eliana and Savoyian comes from my experience with many people in the law enforcement and military communities. As a former crime reporter and current Auxiliary Police Officer with the NYPD, I’ve spent a lot of time in that world, but writing this novel gave me an opportunity to go even deeper. I spoke with detectives, intelligence analysts, military personnel—people who’ve had to make impossible choices under extreme pressure. Their stories didn’t just lead to the creation of Eliana and Savoyian; they shaped the moral fabric of the book. Those conversations reminded me how complex and human the world of public service really is, and how rarely that complexity gets reflected in fiction.

If readers find Eliana and Savoyian interesting, I think it’s because they’re both wrestling with the same question: how do you stay human in the face of inhuman events? That’s the question that drove me to write the book. And I hope it stays with readers after they finish it.

Q: Q: If The Meaning of the Murder and Moments of Doubt were made into movies or TV series, who would be your dream cast to play the characters and why?

A: I don’t have a good answer about my dream cast, but I think the question is entirely understandable. For many authors, maybe all of us, the best thing that could possibly happen to our novel is that it gets turned into a movie. But it’s a peculiar thing, isn’t it? A sculptor doesn’t hope their sculpture will be turned into a painting. No painter hopes their painting will become a dance. And no dancer hopes—well, you get the idea. Yet novelists often hope their novels will be turned into something else entirely.

Of course, the sculpture-into-painting analogy only goes so far, because novels and films are, in fact, deeply united by a crucial common component: telling a story.

But are they telling the same kind of story? Not quite. The easy answer is that novels can explore the inner life in a way movies cannot. But it goes beyond that. I’ve sometimes focused my reading entirely on books that were also films. I think of it as “research.” Sometimes I read the book first, sometimes watch the movie, sometimes read the screenplay. Sometimes I’ll read part of the book, watch part of the movie, then go back to the book. Regardless, what interests me is how the forms differ—and the differences are often profound.

The examples are almost too numerous to begin listing, but a few come to mind quickly.

Conrad’s Heart of Darkness ends with Marlow’s quiet lie to Kurtz’s fiancée—a moment of unbearable ambivalence: is he being merciful or cowardly? In Apocalypse Now, that ambiguity disappears; Kurtz dies, Willard departs, and the story resolves as an allegory of war’s madness. James Jones’s From Here to Eternity—a searing indictment of military corruption—was refashioned in Hollywood as a wartime romance, its brutality softened by iconic images of love and loss. Walter Tevis’s The Hustler hinges on Eddie Felson’s guilt over Sarah’s death; the film shifts the emphasis to triumph at the pool table. Even Delia Owens’s Where the Crawdads Sing, morally ambiguous in print, was reshaped into a more conventional thriller with a tidy twist for the screen.

These transformations remind us that novels and films speak in different dialects of storytelling. The novel lingers, unsettles, and complicates. The film resolves. What often disappears in the passage from page to screen is the moral aftertaste—the silence that continues long after the book is closed.

Now, I probably sound like a literary snob. So just for the record, let me be clear: sometimes, I do think the movie version is better than the book. A few examples that come to mind—The Verdict with Paul Newman, The Firm with Tom Cruise, Forrest Gump with Tom Hanks, The Godfather with Al Pacino, Jaws with Roy Scheider and Robert Shaw.

Bottom line: if someone wants to turn either of my novels into a film, I will be absolutely thrilled. I expect I’ll pretend not to care what they change—while secretly obsessing over every single scene. Yes, of course I have my moral principles. Don’t we all? But I love a good movie.

Q: Will your next book be a sequel to The Meaning of the Murder or will it be a totally different story and characters this time around?

A: I am open to the idea of writing a sequel, but right now I’m deep into the revision process of a novel called The Story of Leaving Hunts Point. It centers on an interracial relationship between a Jewish American businessman and an African American woman—and the emotional, cultural, and political challenges they face when a boyfriend from her past is released from prison and wants to see her again.

Though not a police procedural, the novel draws heavily on my journalism background, including years spent reporting on crime, incarceration, and the probation system. What interests me most are the layers of identity—how race, class, family, and personal history shape not only how we see the world, but how we see each other.