Newsletters

Q&A With Simon Tolkien

New Information about Upcoming Book Related News

Q&A With Simon Tolkien

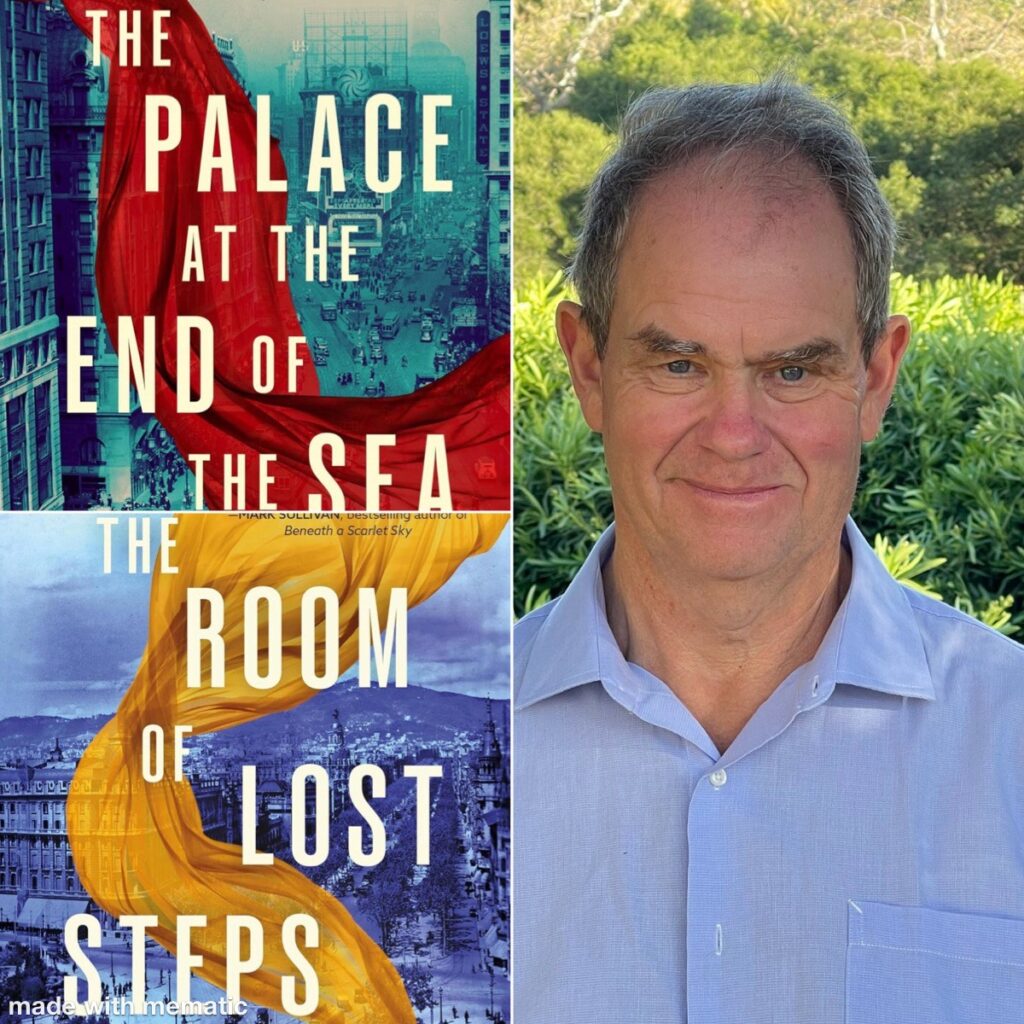

I’m beyond excited and honored to be doing this Q&A with Simon Tolkien. Simon Tolkien is the author of the solo novels Final Witness, & No Man’s Land. Simon’s Inspector Trave Trilogy includes the books The Inheritance, The King Of Diamonds, & Orders From Berlin. His new books are historical fiction which is The Palace at The End Of The Sea & its sequel coming out on September 16th in the US, The Room Of Lost Steps. In the past Simon was a barrister in England & currently he’s the director of the Tolkien estate. Simon is also a series consultant on the Amazon tv series Rings of Power based on the Lord of the Rings world his grandfather J.R.R Tolkien created!

Q: Simon welcome to Book Notions! Can you give a brief description of each of your novels beginning with The Palace at The End Of The Sea?

A: The Palace at the End of the Sea is a coming-of-age story that begins in New York in the Great Depression and ends with a murder in a Spanish village in the summer of 1936. The hero, Theo Sterling experiences family tragedy in America, navigates an alien boarding school in England, and falls in love in Spain, all while searching for an identity in a world in turmoil. The sequel novel takes Theo’s story on through the Spanish Civil War from its outbreak in Barcelona to the battlefields around Madrid and beyond and completes his journey from hope that he can change the world to ultimate disillusionment with the Utopian creeds that had seemed to promise him so much.

Final Witness is about a boy’s quest to find out if his father’s new wife conspired to kill his mother; The Inheritance is a whodunnit murder mystery that Inspector Trave needs to solve before an innocent man is hanged; The King of Diamonds turns on whether a charismatic diamond dealer helped Belgian Jews to escape from the Nazis or betrayed them to steal their jewels, and has now committed further murders to cover up his crimes; Orders from Berlin is about a Nazi plot to assassinate Winston Churchill in 1940, using a mole spy embedded inside the British Secret Service; and No Man’s Land is set in the second decade of the 20th century and tells the story of a young man, Adam Raine, who is torn between warring classes in a Yorkshire mining town and goes on to fight in the First World War.

Q: Reading your bio on your website, you studied history at Trinity College in Oxford, England! What was that experience like?

A: I have always loved Oxford’s beautiful mediaeval architecture and the unique way in which meadows and rivers abound within the city. But my time at college there was troubled: I was underconfident and unsure of who I was, and the three years passed in a whirl of emotion and confusion. I was in search of an identity, and I think my experiences as a teenager and young man have fueled my interest in the coming-of-age stories that have been the focus of my last three novels.

I adored history when I was a boy. My mother had inherited a huge leather-bound book called Haydn’s Dictionary of Dates and I would spend days reading the entries and building pictures in my mind of ancient imperial courts and lonely explorers’ ships battered by ocean winds. The past was another country, as alive as mine, and infinitely more enthralling than the sleepy English village where I grew up. History was my best subject at school, but I was frustrated there and at university by the way it concentrated on the causes and results of events, ignoring the visceral experience of what had actually happened in the heat of revolution or battle. As an author, I began writing crime novels, but history gradually took over, and through historical fiction I finally felt that I had come full circle and found my vocation in life, recapturing that sense of wonder that I had felt as a child, as I try to bring the past to life and convey its magic to my readers.

Q: You also said in the bio on your website that after studying history you reluctantly went to law school to become a barrister & then at age 41 you decided to take the plunge to become an author. Were you scared to make that transition or were you more excited or both?

A: I have had a much stranger career than I would have anticipated when I left Oxford in 1981. I do remember thinking that I was putting on a straitjacket when I followed my father’s advice and went to law school. I felt that I was giving up on my creativity, but I also had to admit that I didn’t know how that was going to earn me a living. I was confused, and one of the only things I was sure of was that I couldn’t write fiction! To begin with, lawyering was everything I feared – dull days conveying real estate and writing wills! But then I stumbled into crime and loved it. The legal profession in England is split between solicitors who prepare cases and barristers who present them in the higher courts, and I decided that I wanted to be the one out there in front of the jury, so I switched to becoming a barrister in a wig and gown. The work was stressful but exciting and gave me a new sense of self-confidence that ultimately led me to question my self-imposed limitations. The creativity that I had long kept suppressed, forced itself to the surface; I turned forty and the world turned two thousand; and I picked up my pen.

Q: Is it fair to say that your time studying history at Trinity College & also being a barrister, helped with writing your books? I ask because there are authors who say the famous saying write what you know.

A: I think they’re right. I was unsure of myself when I began writing fiction, particularly as I had had no training in how to do it! I instinctively felt I needed support structures, and I began with crime novels because I knew the world. My first two books were also courtroom dramas because the language and setting were so familiar to me, but I then came to feel that the medium was inhibiting my writing, and that I wanted to paint on a broader canvas. I stayed with crime, but elements of history crept in. Both The Inheritance and The King of Diamonds had Second World War back stories, and with Orders from Berlin, I went further back in time and set the book in the middle of the London Blitz. All these books depended on suspense, and the big change for me came with No Man’s Land where I felt I had come far enough as a writer to make character development the vehicle for story advancement as opposed to the dictates of the plot. My books got longer, history replaced crime, and I became a fully-fledged historical fiction writer.

So, to answer your question, I think that my work as a criminal barrister has helped me enormously with my writing career. It gave me subject matter and language when I needed it; and with my more recent books, the ability to organize and filter information has underpinned the research process which now takes me as long as the writing. My love of history has been vital too, but I relate that more to my childhood than my experience of the academic subject for the reasons given in my answer to your second question.

Q: Since The Palace At The End Of The Sea & its sequel The Room Of Lost Steps are both historical fiction novels, how long did it take you to research and write both? Since both of those novels discuss the Spanish Civil War, did you make a trip to Spain as part of your research? If so, what was that like?

A: The books took seven years to plot, research, write and edit. The research took about as long as the writing. The story takes place over a period of nine years and is set in America, England and Spain, so there were many different topics I needed detailed information about. I read all I could about New York City in the Great Depression and English boarding schools in the Thirties, and about what life might have been like in a small Andalusian village of that period: a world governed by ancient customs that hadn’t changed since mediaeval times, but that no longer exists.

The politics of the Spanish Civil War were exceedingly complex, which no doubt explains why novelists since Hemingway have avoided the subject, and I worked hard to understand how and why relevant events happened, helped immeasurably by the ten days I spent in Barcelona visiting all the locations that appear in The Room of Lost Steps, so that I would be able to see them in my mind when writing those chapters. I read the long-forgotten accounts and letters left behind by the brave young American men who volunteered to cross the sea and fight with the International Brigades, and I studied Communism and Fascism, Catholicism and Anarchism, trying to build as complete a picture as I could of that vanished era that I wanted to bring faithfully to life.

Q: Since J.R.R. Tolkien was your grandfather, did you feel immense pressure just as good as he was as an author?

A: I loved my grandfather when I was a boy, and his legacy brought me gifts that I am very grateful for. It’s not at all his fault that the Tolkien relationship has caused me difficulties in my life. For many years, I felt overshadowed by the magnitude of his literary achievement, and I am sure that this contributed to my long-held conviction that I couldn’t write fiction. My search for my own identity certainly wasn’t helped by being ‘the grandson.’ This all began to change when I became a writer myself, and reached fruition with the publication in 2016 of No Man’s Land, in which I brought to life the experience of the British soldiers like my grandfather, who fought on the Western Front in the First World War, and came to understand the profound effect that the war had on his imagination. I felt that the book honored his memory, and that he would have been proud of me. At last, my grandfather and his achievements had become an inspiration to me and not a block to my self-expression, and I felt I was standing beside him and not behind him.

Q: Are you currently writing another sequel to The Palace At The End Of The Sea & The Room Of Lost Steps? Or will it be a standalone novel with a different story and characters?

A: No, Theo Sterling’s journey is complete, as it should be after all the years we have spent in each other’s company, and I must find a new subject and hero to work with. Plotting is in some ways the hardest part of the writing process. Ideas come slowly, and there’s always the accompanying uncertainty about whether they are going to work in the context of a full novel. I am still very much in the early stages, but my instinct is to set my next book somewhere in occupied Europe during the Second World War. I am fascinated by how different people – both those from the native population and agents sent in from outside – respond to occupation and repression, and I would like to explore why some collaborate or do nothing, while others risk their lives and those of their friends and families to resist.