Newsletters

Q&A With Frank Abe

New Information about Upcoming Book Related News

Q&A With Frank Abe

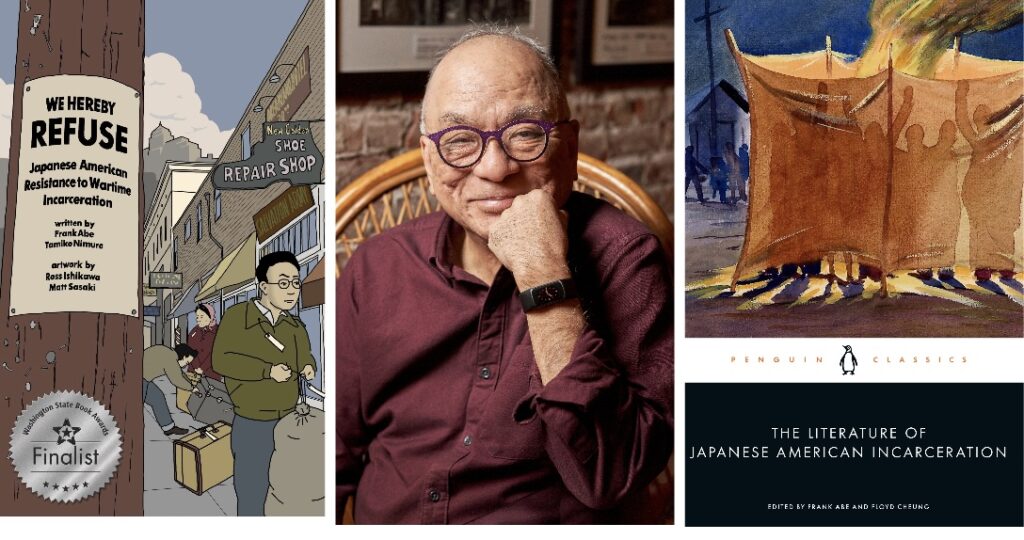

I am so glad that Jeffrey Yamaguchi was able to connect me with author & editor Frank Abe for this Q&A. Frank is lead author of the graphic novel We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration, and writer and co-editor of The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration & John Okada: The Life and Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy. Frank also wrote, produced & directed the award-winning PBS documentary Conscience and the Constitution on the largest resistance movement to incarceration camps!

Q: Frank, would you please give a brief description of each of the books you wrote and edited starting with your recent release The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration?

A: Each of my books reclaims and reframes the wartime narrative of Japanese Americans by showing just how they pushed back and contested the injustice, whether through direct action or the act of writing. Penguin Classics of course is known for publishing quality anthologies that contextualize important historical periods for a modern audience, and The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration captures the collective voice of the people in camp by eschewing familiar selections in favor of writings that have been long overlooked on the shelf, buried in the archives, or languished unread in the Japanese language. It’s now in its third printing.

Chin Music Press of Seattle, I just learned, is preparing a fourth printing of our graphic novel, We Hereby Refuse, which presents the story of camp as you’ve never seen it before, through the eyes of three young people who refuse to submit to their ongoing imprisonment in American concentration camps without a fight.

Our anthology on John Okada includes the first-ever biography of the author of the foundational novel, No-No Boy, along with short stories, magazine satires, and a short play that has not been seen for 70 years.

Q: What was it like writing, producing & directing the award-winning PBS documentary Conscience and the Constitution?

A: I really had no business setting out to make a film as I was a radio journalist, but this story of the largest organized resistance to wartime incarceration clearly needed the narrative reach of the visual medium. I was fortunate to share this vision with playwright Frank Chin and our mutual friend, videographer Phil Sturholm. We just dove in on a shoestring and interviewed those surviving members of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee who had spent two years in camp and two years in federal prison and were willing to speak in public. It took eight years for me to learn how to write and produce a film, build the story around the interviews, and then navigate a path to broadcast. Finishing funds from the Independent Television Service (ITVS) enabled us to hire a film editor, the first African American woman in the American Cinema Editors guild, Lillian Benson, A.C.E., who turned our footage inside out to make it an effective piece of visual storytelling suitable for national PBS. If any of that piques your interest, you can watch the film on Amazon Prime.

Q: I think it’s important to learn from history so that we aren’t doomed to repeat it, would you say that is the lesson you want readers to learn after reading We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration & The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration? What emotions do you hope readers feel after reading your books?

A: What I hope readers take away is empathy for people they don’t know, for those who are not like them. It was fear of “the other” that enabled this nation to forcibly remove completely innocent people from their homes and lock them up in American concentration camps solely on the race they shared with a wartime enemy. We flatly call the last section of our Penguin Classics anthology “Repeating History,” because it’s too late to talk about “learning our lessons” not to repeat such actions. If anything, the precedent of interning Issei community leaders and heads of households – immigrants from Japan who were denied the chance to apply for naturalized U.S. citizenship because of racial bans – is now cited by the president-elect as the basis for his program of mass deportation of undocumented immigrants. And we’ve seen this before: the election of 2016 enabled travel bans from majority-Muslim nations, separations of families seeking asylum at the southern border, and kids in cages. This is no longer ancient history; this is the America voters have chosen today. In our anthology, we quote the prescient words of journalist James Omura from 1942, “Has the Gestapo Come to America?”

Q: If you are currently writing another book, is it like We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration & The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration? Or will it be something like that biography you edited John Okada: The Life and Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy?

A: I’m continuing to explore the voice of John Okada, whose underlying message of resistance to the tyranny of fear and ignorance suddenly has a new context in addressing the present moment. I’ve been commissioned to adapt his novel for the stage, with interest from a major regional theater. The project has just taken on a new urgency.

Q: What advice would you give to anyone wanting to have a career in writing and editing?

A: Just write. Write what you know. Find the thing that captures your imagination, dig into it, and write about that. Work by day and write at night. Don’t start off trying to earn a living by it until you feel you’ve found your voice and found a way to have it land with an audience.

I think every writer takes a different path. I had a goal but not a plan. After training as an actor and director, I wanted to learn how to write so I got a job in radio news, reasoning that radio depended strictly on the written word. That forced me to write quickly and on deadline, eight hours a day, to learn what an audience needs and how to write for the ear, not for the page. That led to a second career as a communications director in local government, framing the messages and stories I wanted journalists to write. All through those decades I pursued the things important to me at the time — helping found an Asian American theater, winning redress and reparations for the camps, writing and producing a film on resistance to the camps, teaching journalism. I pursued people in my fields of interest and by instinct and luck found myself often to be in the right place at the right time.